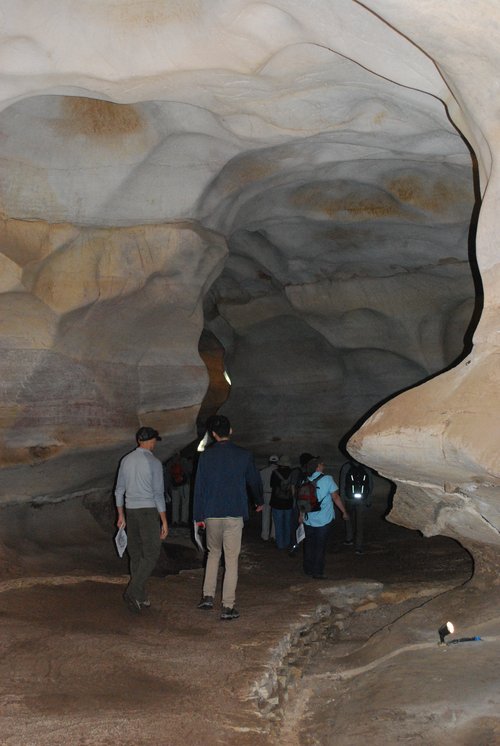

Cave formed by the flow of groundwater at the water table (phreatic cave), Longhorne Caverns, Texas

The high volume of pore space in carbonate rocks means that they form important aquifers in many countries, critical to the supply of freshwater. The groundwater in parts of the England comes from carbonate aquifers, for example around the ‘White Peak’ area of Derbyshire, north Yorkshire and the Mendip Hills. This gives us ‘hard’ water, which has high concentrations of calcium and magnesium bicarbonates that precipitates as a finely crystalline scale within pipes and domestic appliances. Water in these aquifers travels via underground caves and fractures before emerging at the surface as springs. The complex connectivity of caves and fractures in the subsurface can make it difficult to map the flow of groundwater in these aquifers, and water flow and discharge can also change quickly and dramatically after heavy rain.